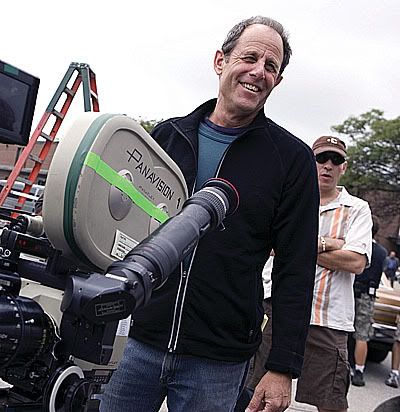

I had the opportunity to interview Abraham last month when he was in Easton, Md., for the movie’s premiere on opening night of the first-ever Chesapeake Film Festival.

Greg Maki: You’ve been a producer for a number of years. Were you looking to direct a movie or was it this in particular that made you say, “I want to direct?”

Marc Abraham: I started out as a writer and I always start on the more creative side of things. I became a producer almost by accident. I started a company that I thought was actually gonna be so I could write and direct my own films and I ended up producing a lot of movies. I always wanted to stay on the writer-director side, but things got good and I started producing a lot of movies and pretty soon that’s what I was doing. I always figured at one point I’d go become a director and direct a picture. Like anything, it’s just really finding something that you care about and you want to do. I just fell in love with the story. I read the story. John Seabrook wrote it in The New Yorker and I read it about three or four years after he had published it. I just was completely besotted by the piece. I love stories about the common man, I love stories about the average Joe. One of the producers, Mike Lieber, and John and I talked, and I said, “I’m gonna tell you something. Here’s the good news for you guys: I’m gonna option the material and develop it into a movie. And the bad news for you is I’m gonna direct it.” They were stuck because they wanted me to buy it. They said, “Oh yeah, that sounds like a good idea,” never probably even really thinking it would happen or certainly not gonna tell me they didn’t think it was a good idea. And Greg, I just stayed with it.

A lot of things came and went. I developed the material. It went from a gestation period into something that was full-fledged for me, and then finally I just got to the point where I was ready to move forward. I just said, “You know what? The time has come. If I’m ever gonna do this and quit talking”—and I’m the kind of person who doesn’t like to talk about things much, I like to do ‘em. And I was finding myself talking a lot about directing movies, but not doing it. I just sort of focused on it. That was about, actually, sadly around the time Bob died, three years ago. Once I put my mind to it, I started making the movie pretty quickly. It was something I’ve wanted to do, in a short form to your question, and it was also that I needed something I was passionate about and this fit the bill.

Was Dr. Kearns involved with it at all before he passed away?

Before he passed away, he had obviously given us the rights to the story and he had gone along with that. He had actually talked to the writer extensively and they had videotaped some stuff together with Bob and his family. So yeah, he was definitely involved. I think he was a little cynical about the idea of whether it would happen or not, but he was involved. By the time I started getting really serious about directing it, he had passed away. There’s nothing profound about this, it’s just life: There’s all these things that you think will happen in a certain way and, of course, they never happen that way and we know that. That’s the nature of the deal. But I kind of always thought I’ll make this movie and Bob Kearns will see it and he’ll finally get his due and he’ll feel completely vindicated. Of course, I did end up making the film and he’s gone. So he didn’t get to see it. But the great news is his kids have and it’s meant so much to them. You’ve probably talked to them and if you certainly see ‘em, they’ve been transported by the experience because it’s their lives and they’re on the movies and they’re being played, and it’s sweet. There’s an innocence to their reaction and naïveté, but it’s also something that I feel really happy that I was able to help them experience.

Tim Kearns said it sends chills up his spine and he said something like, “Your life isn’t supposed to flash before your eyes until you die.” He said it was eerie how close it was.

Well I attempted to keep it really close and Tim’s a really smart guy. He was very helpful and so was Bob Jr., who’s here tonight. All of the family, all of the kids were really good. They were very helpful and they weren’t interfering. I told them from the beginning you can’t have any control. I won’t make a movie with people having control. By nature of making films or any form of art, you’re gonna have to squish it and move it and turn it from a square to a trapezoid. That’s the nature of it. All art’s an interpretation. All life is. Documentaries aren’t the truth. Michael Moore makes a documentary and 50 percent of the country thinks it’s the truth and 50 percent of it says, “That’s not what it is.” It’s an interpretation. Certainly, with a feature film it’s the same. I endeavored to keep it really close. They seem to really be happy and they certainly were helpful.

How much of a challenge was it to make a movie where your main character is not always a likable guy?

It’s a challenge because you have to be committed to making that happen and the thing about it, you see, that’s why I love the movie. I wouldn’t have really been interested, nor do I believe in life like that. I don’t think that life is black and white. I don’t think people are saints. I don’t think saints are saints. I don’t think anybody’s all good and I don’t think most people, for the most part outside of a few exceptions, are really all bad. So I wouldn’t have been interested in the character that I was gonna have to paint as lily white. That, to me, is boring. It just doesn’t give you any insight into the human condition.

What I loved about the story was that I had a character who was flawed, a guy who was fighting for injustice, fighting for principle but at the same time was taking it pretty far, a man who was willing to sacrifice, potentially, his family and his children in some ways or certainly his relationship with his children. That’s what fascinated me and that was the challenge.

When Greg and I first talked about the movie, one of the first things that we both agreed upon and why were so certain we were the right team was that neither one of us wanted to whitewash the story. He was intent on playing him with all the flaws and I was certain that that’s how it had to be. The idea of Bob Kearns as some saintly and altruistic character—not interesting. Bob Kearns who’s both fighting for some principle but is obsessed, Bob Kearns who’s almost suffering from an addiction in my opinion, a guy who presses your buttons way more than you want, a guy who’s putting sometimes being reasonable completely out of the question, becomes a completely unreasonable man—that’s interesting to me. That was the challenge and I think that’s why people respond to the movie, because they don’t think they’re getting played. When people come out of this movie, they feel completely comfortable having an emotional response because they don’t feel like somebody was sitting there (pulling puppet strings). That’s why the response has been generally really, really strong.

It’s very subtle, I think. It doesn’t have the big emotional scenes. Did you have any worries about how that would play to an audience?

You know, I did it the way I thought I wanted to do it. I’ve waited a long time, I’ve produced a lot of movies. I figure if I’m gonna do it, that’s what I like. I’m interested in subtlety. I’m interested in nuance. And I’m hopeful that there are people who respect that. And I’ve found that there are. But you’re right. There’s a lot of restraint in the movie. That’s who I am and that’s the kind of movies that I love. I don’t get emotional in a movie because somebody has a big emotional scene and throws a lot of big music on it. If I get emotional in a movie, it’s because it’s been restrained. I believe restraint is what makes something have a resonance to it. So I didn’t worry about it because I didn’t think about it because I couldn’t have done it another way. It’s not my nature. A version of it that was bigger and broader and more obvious and overt, maybe it would be successful, but I would not be the guy to do it. I just wouldn’t even know how.

I like the subtle, restrained type of stuff, too. It sort of lets you find your own meaning and emotions in it.

Exactly. Then you can interpret it the way you want. The scene on the porch, for instance, which is on the cover of that little dropout section that you guys did or somebody did, which is nice. I love that scene and I love that photograph, so I was pleased that they chose that. It’s a perfect example of this. When I was doing that scene and scoring that scene, people were saying, “You gotta put music in it.” Most movies would put music in that scene. And I said, “No, I’m not putting music in it.” Everybody said, “Why?” I said, “Because the minute I put music in it, someone’s gonna know that scene’s supposed to be important.” And that scene is important because up until that moment, everything’s really cozy. And then she says, “But I think you are successful.” He says, “What makes a man successful?” She says, “But you are successful. Look at what we have and look at us.” And he goes, “Maybe it’s something else.” He doesn’t hear her at all and Lauren’s face just beautifully drops. I said, “The minute I put music in there, I’m gonna tell ‘em what that scene’s about and I don’t want anybody to know what that scene’s about until it’s over with.” When it’s over with, hopefully people will respond to how they felt, rather than what I told them. That’s an example of where you can change those things.

Obviously, you’ve known and worked with directors for years, but having now done it yourself does that give you a different perspective on the process?

Yeah. As many movies as I’ve produced—and I’ve worked with some of the biggest directors in the business, whether it’s Tony Scott or Pete Berg or Brett Ratner or Alan Parker or Norman Jewison or Alfonso Cuaron. I’ve worked with a lot of guys. Sometimes guys, they get pretty rough. I’m not the kind of person that believes you have to be that rough, but I understand now why they got a little rough.

As a producer what you’re trying to do is, you’re often compromising because you’re trying to take the money and the situation and you’re basically saying, “I know we didn’t get you this, but look at”—basically, the glass is half full, and they’re looking at it and they don’t care because they’re going, “No, I didn’t want to shoot in this room. It’s supposed to be in the ballroom of the Four Seasons in New York and I’m in the Tidewater.” It’s like, “No, this isn’t the same feeling.”

The thing you really come to understand about that level of frustration that sometimes can really drive a director crazy is as a producer you have a vision, but you don’t take it completely as far—and I’m a very hands-on producer—you don’t take it all the way because it’s not really you’re responsibility. You’ve handed it off. As a director, every scene, every moment, every action is something that you have envisioned and you have dreamt. And every single minute, your dreams run smack dab into reality at about 85 miles an hour. Every second. Because every second someone’s telling you you can’t get exactly what you want. We’re gonna do this interview. Well I want four people up there. I want to have that television screen on and I want the Ryder Cup to be on while we’re talking and I want to be watching it so I’m distracted so it shows it’s not the thing. I want it to be real like that. And they come and they go, “Marc, we can’t do the Ryder Cup. We can’t get the rights. They won’t let us do the Ryder Cup.” Can we do something else? Can we put a football game on? “Well what football game? Can we put the Allegany State/Fresno State? They’ll give us the rights.” Nobody gives a shit about Allegany State. How about the Colorado/West Virginia game, can we put that game on? “Can’t get that.” It might not seem important and maybe it’s not. Maybe what’s important about the conversation is the fact that I’m distracted. Maybe this conversation is about the fact that we’re really close friends and you just found out that you’re wife’s cheating on you, and I’m a huge USC fan and they’re playing Notre Dame. The game’s on and you’re telling me this and I want to care because you’re my buddy and your wife is cheating on you, but I’m (watching the game). Well if it’s Fresno State/Allegany State, who gives a shit? That makes no sense. If I’m a big USC fan and that’s a USC game, then that scene has crazy tension.

I don’t mean to belabor the point, you understand what I’m saying. That’s what you hear every day. “We can’t get you that. We can’t get you that. Well that we can do.” You come to appreciate that as a director it’s not your job to compromise and also that you’re basically gonna get a lot of bad news.

Are you planning to direct again?

Yeah.

Do you know what’s next?

I don’t, really. I’m looking. It’s hard to find something that you’re passionate about and I was really passionate about this story. I really was. It just was one of those stories. I never forgot it and I never let it go. I hope I can find something I feel that same way about. If I can’t, I’ll find something that I’m close to, but I really did love this story.

Who would’ve thought there would be such a story behind windshield wipers?

Exactly. That’s what I love about it. When people talk and they go, “It’s this story about this man who invented the intermittent windshield wiper,” and everybody laughs. But, of course, it’s not a story about a man who invented windshield wipers. What I love about it is the juxtaposition of what’s a seemingly trivial idea with a huge idea. It’s about one of the great themes in literature—injustice and principle. That’s not easy to come by. What makes people kind of go like “who figures?” is exactly what I fell in love with. So I hope I find something soon. I really loved doing it.

Do you have anything you’re producing coming up?

We’ve got a remake of Creature from the Black Lagoon that we’re trying to do in kind of an interesting, new way. We’ve got a Robert Ludlum novel called The Sigma Protocol that the guys who wrote Iron Man just turned in a draft of that we’re excited about. It’s kind of a good popcorn movie, smart, in the Bourne vein. And then I’ve got a pretty serious movie based on a true story called The Dallas Buyer’s Club that Craig Gillespie who directed Lars and the Real Girl is gonna do again with Ryan Gosling. So I’ve got three things there that are percolating.

Do you enjoy coming to these festivals?

When you make a movie, you’re a little bit like a politician. If you’ve got Batman, you don’t come to this festival because you don’t have to come to the festivals. It’s not like you don’t want to, but you don’t do it. When you have a movie like this, you’ve got to get out and beat the drum. I’m passionate about the movie and I want it to succeed because I want people to see the picture. So yeah, I’m a very curious person and I like to go to new places and I like to meet people. It’s exhausting. I was in Atlanta two days ago. I was in L.A. three days ago. I was in Boston one day ago. I’m in Baltimore all day today and down here in Easton. Tonight, I’ve got to drive all the way back to Baltimore. I know you drove up to see the movie, which I appreciate. I do because now I know how far it is. And then I’ve got to fly back to L.A. Saturday. I’ve got a bunch of kids, they’re missing me. I’m there Saturday, Sunday. Monday, we have a premiere in L.A. and then on Tuesday I fly to Dallas and Wednesday Chicago and Thursday Seattle, come back and then go to New York. So I’m little bit like a politician. I’m kissing babies.

2 comments:

Interesting story and a nice interview.

A really great blog and that was a nice interview about robert kearns and the movie "flash of genius". I have great respect and admiration for dr. kearns. A lot of people could learn something from him about not giving up...or in...no matter what the circumstances are. Take care.

Post a Comment